Understanding the thermal expansion of glass and ceramics is critical in high-temperature applications, materials selection, and product reliability. This technical guide explains the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), Glass Transition Temperature (Tg), Dilatometric Softening Point (Ts), and how these properties are measured using pushrod dilatometer testing.

Thermal Expansion of Glasses and Measurement Method

Temperature is a measure of the heat content of something, for example, the outside air, water in a bathtub, or the middle of a hamburger on the grill. Both practical experience and fundamental physics teach us that heat (a.k.a. thermal energy) moves from a hotter object to a cooler object. Whether a substance is a solid, a liquid, or a gas, its temperature rises as it absorbs heat. In this way, all materials can be thought of as heat batteries that store thermal energy.

Materials absorb thermal energy by converting it into a form of kinetic energy, meaning that the atoms in a substance move around faster as they heat up. For liquids and gases, where the atoms are not strongly bonded together, there is a large change in volume with increasing temperature. If a liquid or gas is confined within a fixed volume during heating (e.g., a sealed container or pipe), then the pressure inside the vessel builds along with the rising temperature.

Unlike liquids or gases, atoms in solids are bonded together more tightly and cannot freely move around to fill available open space. These bonded atoms form a rigid network (a.k.a. a lattice) where thermal energy is stored as wave-like vibrations. At absolute zero, there would be no heat energy available to cause vibrations, and each atom would remain stationary at its equilibrium position. But at temperatures above absolute zero, each atom vibrates around its equilibrium position. The magnitude of these vibrations increases as the temperature is increased and more thermal energy is stored in the atomic lattice. At a sufficiently high temperature, the stored energy / vibration is large enough to break the atomic bonds, the lattice is destroyed, and the material melts and behaves as a liquid.

Due to the nature of atomic bonding, the time-averaged distance between bonded atoms increases with rising temperature. As the distance between bonded atoms decreases, the electrostatic repulsion between their positive nuclei increases more quickly than the increase in attractive forces wanting to pull them together. For all but a small number of special materials, the overall dimensions of a solid object will increase when heated. The degree to which a material expands with rising temperature is a very important property, one which has practical performance implications in the real world. For machines, tools, and assemblies, it is important that the spacing and tolerances with which the components were designed to fit together are adequately maintained over the expected temperature range of use.

Ceramics and glasses are often used at high temperatures due to their ability to withstand heat. Many ceramics objects have a protective coating, or glaze, on their surface, or they might have an internal, glass-containing bonding phase (think “high temperature glue”) which helps hold the ceramic object together. Being bonded together, it is crucial that these different materials have similar thermal expansions, otherwise destructive stresses could develop and lead to crack formation and perhaps total mechanical failure.

Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) in Glass and Ceramics

For glass manufacturers and ceramic engineers, accurate CTE measurement of glass is essential to prevent thermal stress, cracking, and mechanical failure in bonded assemblies.

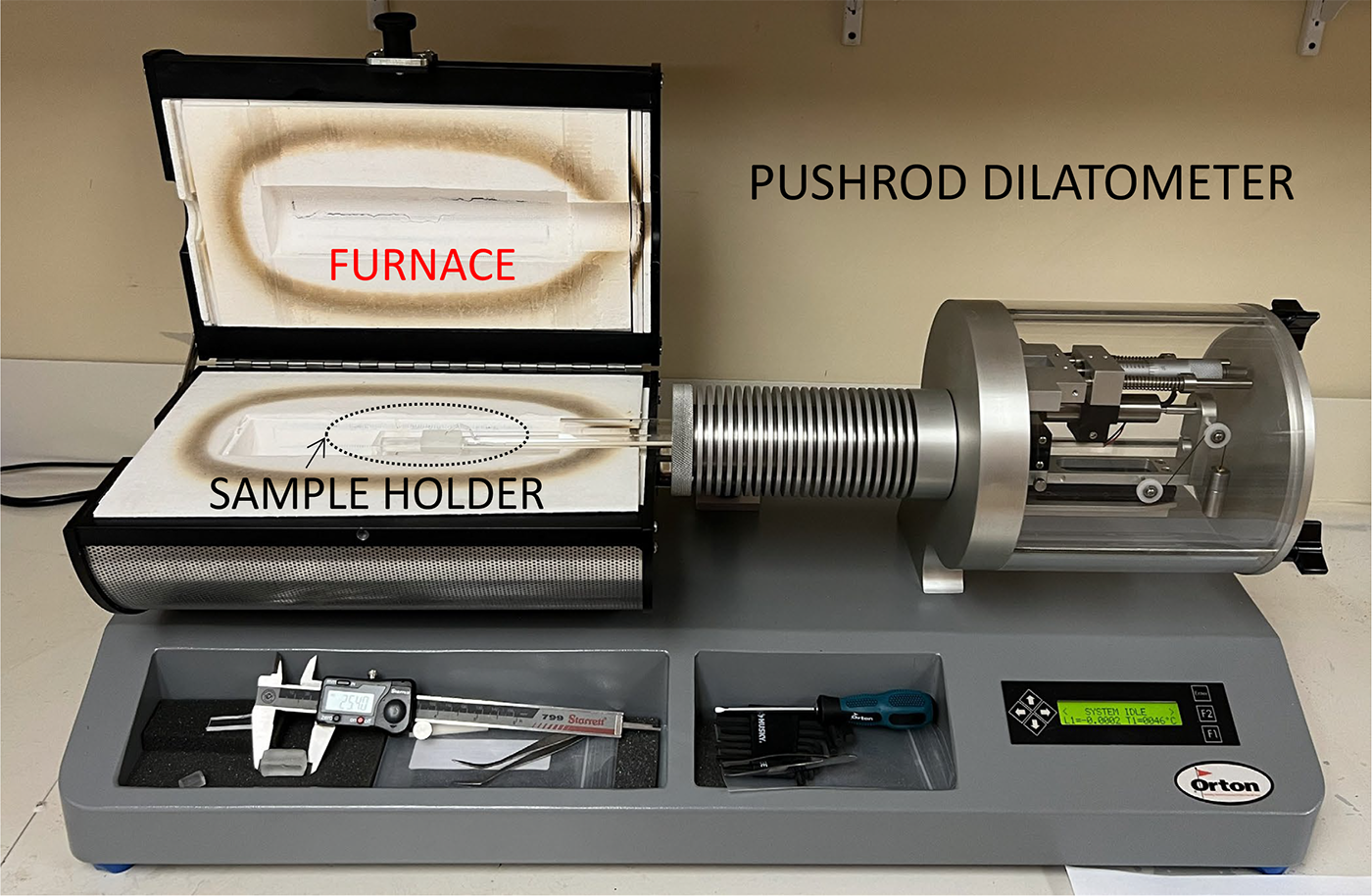

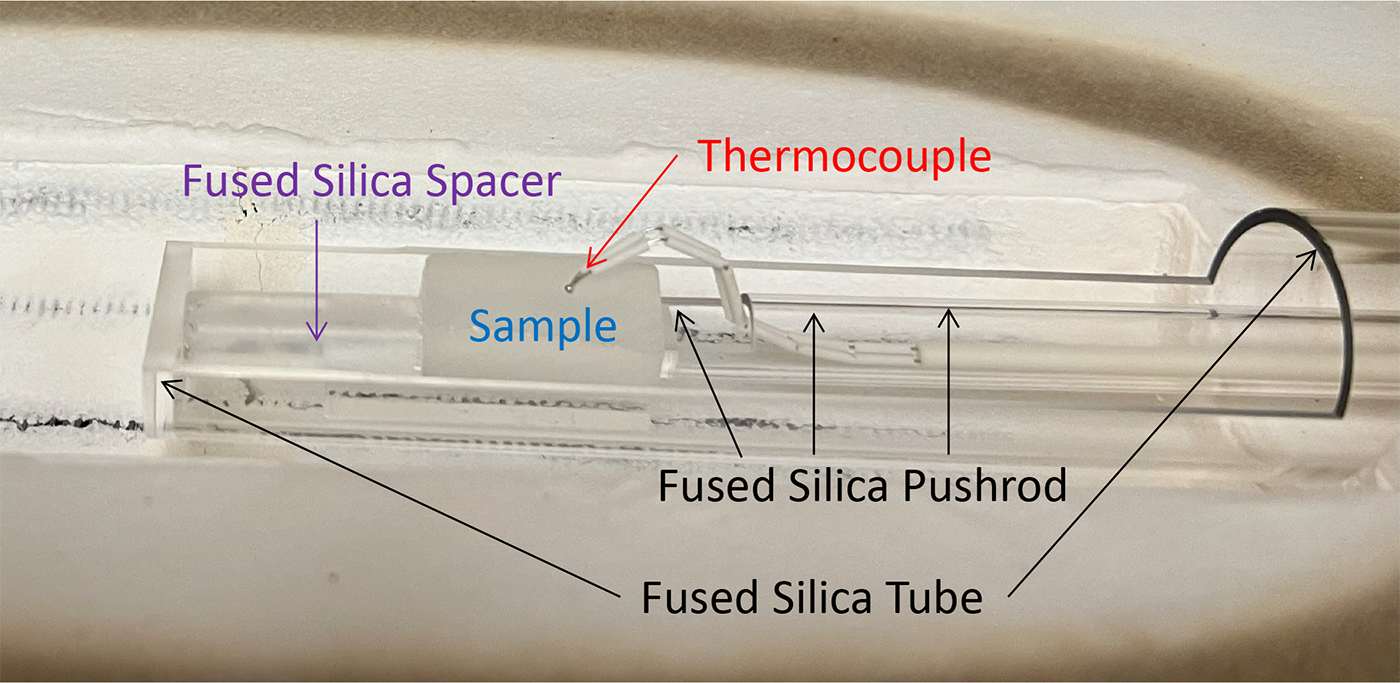

The thermal expansion of materials is the rate of length change with temperature, often expressed as the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), and is measured using an instrument known as a Pushrod Dilatometer. These instruments include a furnace, sample holder assembly and movement sensor that collectively measure the change in sample length during heating over a temperature range. The sensor detecting length change is known as a Linear Voltage Differential Transformer (LVDT), and this device converts a linear displacement of the sample into an electrical signal. The LVDT is mechanically coupled to the sample via a pushrod made from a very low CTE and/or non-reactive material, such as fused silica. Dilatometers must be calibrated using a standard sample to remove the sample holder assembly expansion from the raw data to yield the true sample expansion behavior. Oftentimes aluminum oxide, also known as alumina, is used as a standard sample due to its consistent and reliable expansion behavior.

How Thermal Expansion Is Measured: Pushrod Dilatometer Testing

This method is commonly referred to as dilatometry testing or thermal expansion measurement in high-temperature materials testing laboratories.

Fusion Ceramics has a Dilatometer Model DIL 1410STD manufactured by the Edward Orton Jr. Ceramic Foundation. Pictured in Figure 1, this instrument can reach temperatures of 1000°C and enables precise measurement of CTE for ceramic and glass samples. Proper sample preparation is required to ensure accurate and repeatable measurement, and this step usually involves cutting a small bar of the sample material ( e.g., ¼” x ¼” cross-section) to a standard length (1 cm, 1”, or 2” long) and then grinding or polishing the end faces so they are parallel.

Figure 2 provides a close-up of the sample and sample holder assembly, which is composed of fused silica. A thermocouple passing through the pushrod tube is in contact with the sample to obtain an accurate temperature reading during the measurement.

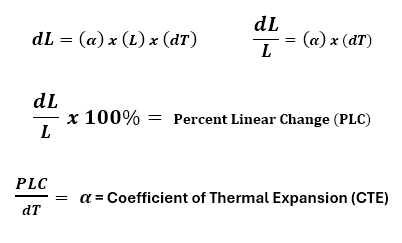

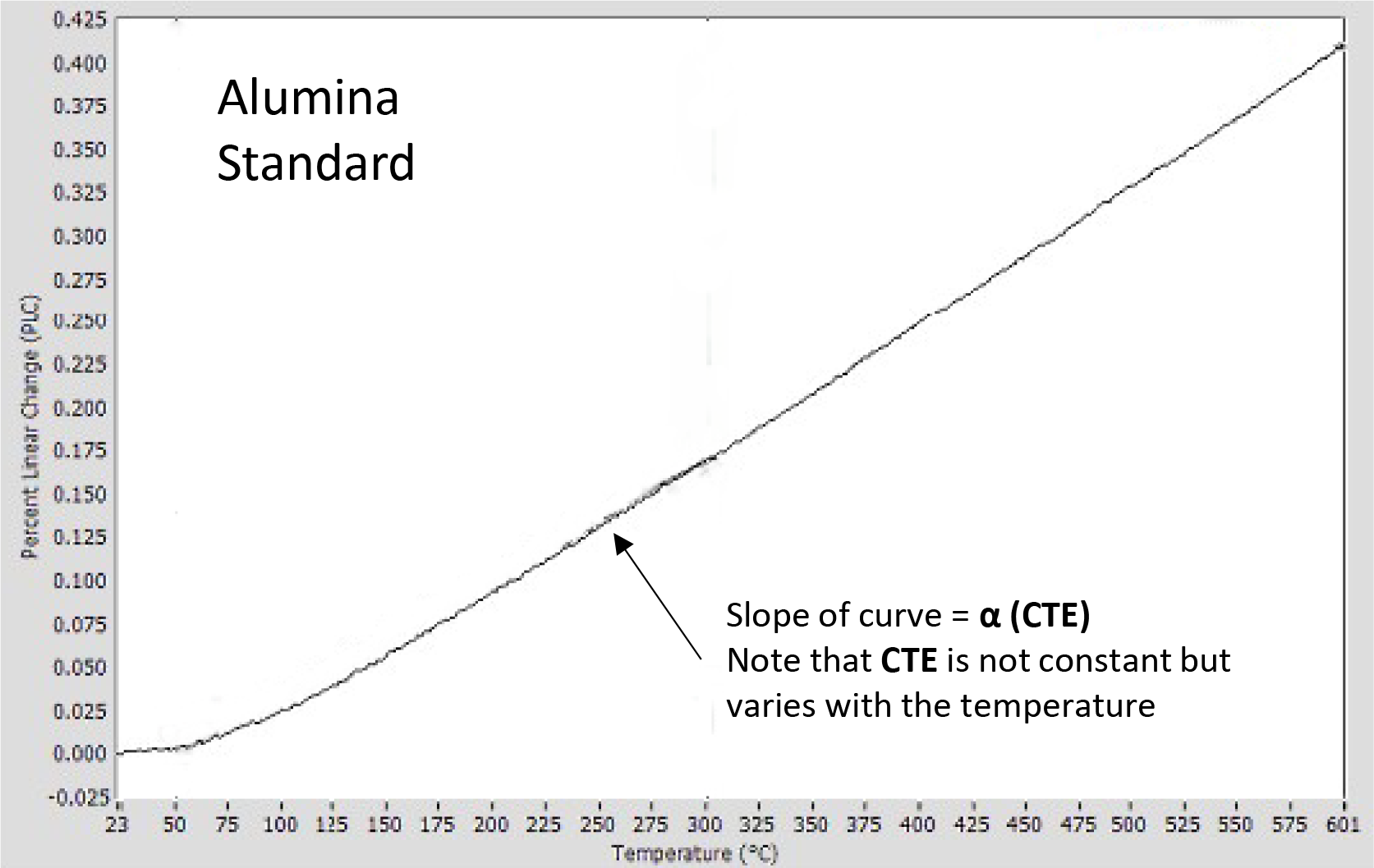

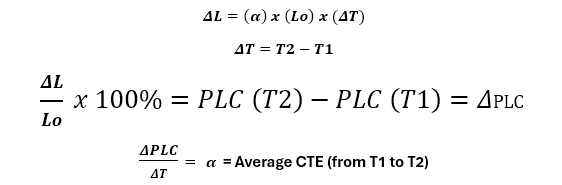

A thermal expansion curve for an alumina standard, shown in Figure 3, plots the sample length versus temperature. In this format, the vertical axis is the Percent Linear Change (PLC) while the horizontal axis displays the temperature. Traditionally, the CTE is represented by the Greek symbol α, and is the derivative or slope of this curve, expressed mathematically as:

- dL is the instantaneous change in length.

- L is the instantaneous sample length at temperature T.

- dT is the instantaneous change in temperature.

- α has units of 1/°C or 1/°F depending on the temperature scale used in the measurement.

- α is often expressed in parts per million (ppm), for example 33 x10-6 /°C or 33ppm/°C.

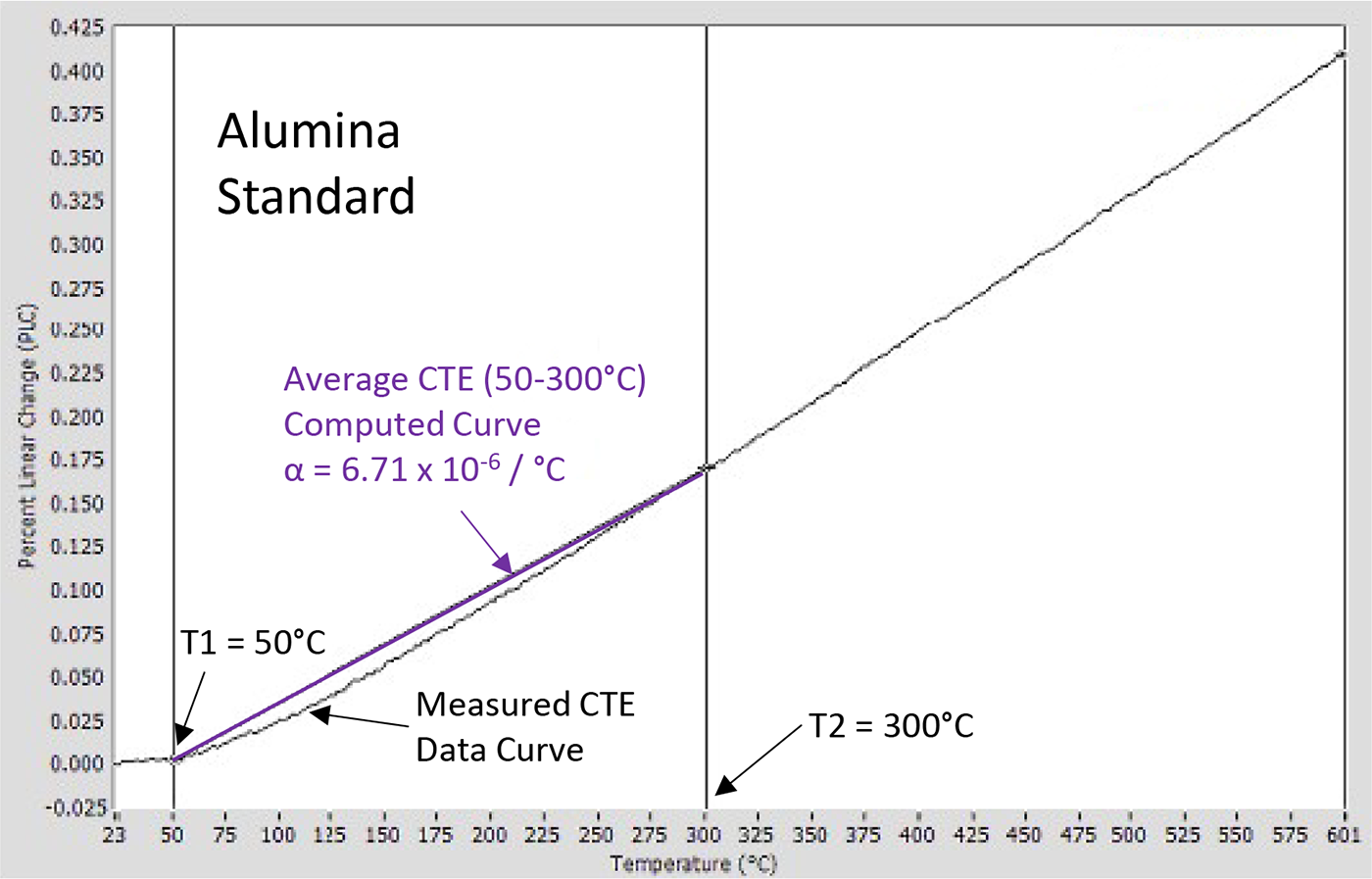

Figure 3 shows the PLC for an aluminum oxide (alumina) standard sample; alumina is used as a standard because it has a relatively constant CTE and is not reactive, even up to high temperatures. As is typical for most materials, the alumina CTE increases with temperature, meaning the slope of the expansion curve is seen to increase slightly with temperature.

It is common to measure the total length change for a sample over the expected operating temperature range, and so the average CTE can be calculated from this data using the expression:

- ΔL is the length change over a temperature range, in this example, T1 = 50°C to T2 = 300°C.

- Lo is the initial sample length at 50°C.

- ΔT is the temperature change over the range of interest, 300°C - 50°C = 250°C in this example.

Figure 4 below shows the difference between the actual expansion at a given temperature for an alumina standard and the average thermal expansion over the temperature range of 50°C to 300°C.

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) and Viscoelastic Behavior

The Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) is one of the most critical material properties in glass engineering because it marks the shift from rigid solid behavior to viscoelastic behavior.

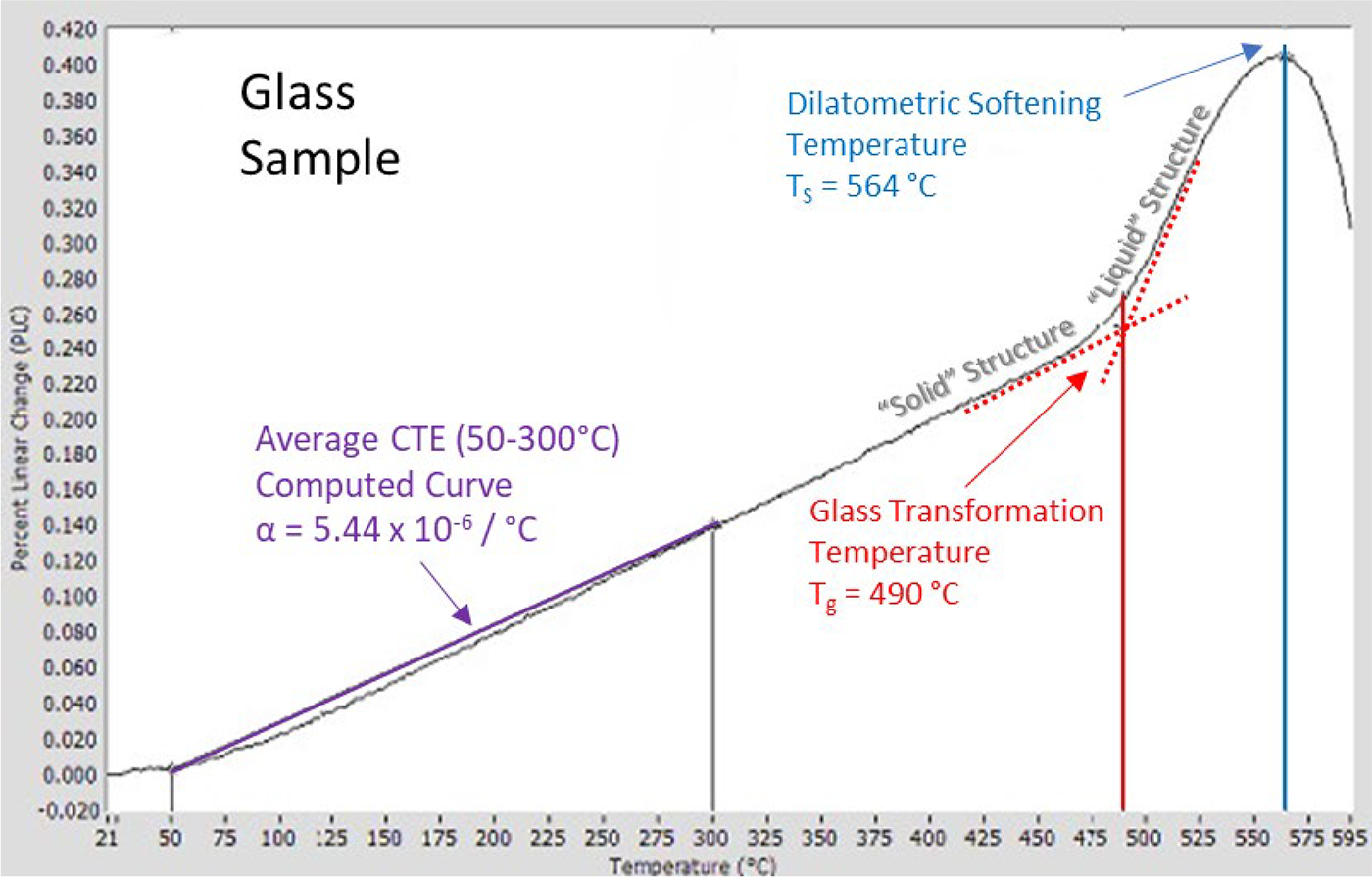

For glass samples, the dilatometer data permits the determination of other important glass properties, namely the Glass Transformation Temperature (Tg) and the Dilatometric Softening Point (Ts). In order to understand the significance of these two properties, we must take a closer look at glasses and what makes them different from other materials.

Most solids are crystalline, meaning their atoms are arranged in 3-dimensional lattices with long-range order, where the lattice position of an individual atom is precisely defined according to a repeating, or “periodic”, sequence. Most solids are also elastic, meaning an external applied force causes an instantaneous strain in the lattice, but this distortion is instantly and fully reversed once the force is removed. One can imagine the lattice as a rigid spring structure that absorbs external force by straining and then returns to its original shape once the force is removed. Some solids behave elastically at small strains but permanently change shape if a threshold strain level is exceeded. Permanent shape change under load, also known as plastic deformation, is a well-known property of metals and polymers, while most ceramics and glasses will deform elastically until fracture occurs. Liquids have no lattice structure and are fluid, so they change shape, or flow, under an applied shear force. This movement by the liquid tends to dissipate the applied force, and the resistance to shear force is called the viscosity, with thicker, slower liquids acting more viscous than lighter, thinner liquids. Sometimes the term fluidity, which is the inverse of viscosity, is used to describe liquids. Because it is measured over time, the magnitude of the viscosity gives insight into how quickly an applied shear will be dissipated; high viscosity fluids require more time to dissipate a given amount of shear, while thinner fluids will accommodate the shear more quickly.

Most glasses are mixtures of ceramic oxides and minerals that have been melted at high temperature to form a liquid. During melting, the bonds between atoms are broken, and the periodic lattices of the starting materials are destroyed. If this liquid is then cooled rapidly enough so that the atoms are unable to settle back neatly into a periodic lattice, the solid lattice that does form is disordered and lacks long-range order. This disordered solid structure is reminiscent of a “frozen liquid”, and glass has been described as a solid material with a liquid-like atomic structure. One result is that unlike crystalline materials that melt at a single temperature known as the Melting Point (Tm), glasses slowly soften and “melt” over a relatively wide temperature range commonly known as the Glass Transformation Range or Glass Transition Region. In this temperature zone, a glass is characterized as a “viscoelastic” material, meaning the response to an imposed stress will be a combination of elastic (instant strain) and viscous (strain over time) behaviors.

When heating up through the Glass Transformation Range, the properties of the solid glass gradually start changing to the fluid-like behaviors normally associated with a liquid. For example, the thermal expansion of a solid increases significantly once it melts and its lattice bonds are broken. The same material, once melted, will expand faster with further heating. Similarly, the thermal expansion for a glass increases markedly in its Glass Transition Region, which is characterized by a Glass Transition Temperature (Tg). The thermal expansion curve for a conventional glass is shown in Figure 5. The Tg is typically found at the intersection of the two tangent lines (red dotted lines) drawn to the curve in the “solid” and “liquid” regions. The measured Tg for different glasses gives insight into the transition from solid to liquid behavior and aids selection of the best candidate glass for a particular application.

Glass Viscosity and High-Temperature Performance

Understanding glass viscosity across temperature ranges is essential in high temperature materials testing and in applications requiring controlled flow during bonding, sealing, or glazing operations.

Another important and related glass property is the viscosity, or resistance to shear flow, which has the SI units Pascal-seconds (Pa·s) or traditional units Poise (P: 1 Pa·s = 10 P). It is common to see viscosity reported in centi-Poise (cP) because water has a viscosity of 1cP at room temperature (20°C). Everyone knows that pure honey is “thicker” or more viscous than water at room temperature, having a typical viscosity of 150-200 cP (20°C) depending on the type of flower the bees were visiting.

We also know by experience that heating thick fluids, such as maple syrup, makes the fluid “thinner” and easier to pour. The viscosity is: (1) a material property of a liquid, (2) is temperature-dependent, and (3) it must be observed or measured over time.

Maple Syrup Viscosity

| Temperature (°C) | Viscosity (centipoise, cP) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 2,000-3,000 |

| 20 | 150-200 |

| 50 | 50-100 |

Solids are rigid

Solids are rigid and do not flow like liquids, so discussing the viscosity of a rigid solid makes no sense because you cannot measure it. The dilatometer is the perfect instrument to follow a glass sample as it transitions from a rigid solid to a viscous material with a measurable viscosity. At the glass transition, vibrations due to the available thermal energy begin to break some atomic bonds in the solid, and the structure starts becoming more liquid-like and flexible, resulting in the noticeable increase in the thermal expansion seen in the dilatometer data. At this point, the glass is still acting like a rigid solid, and it does not flow perceptively. This makes viscosity measure difficult at Tg, although it can be estimated, and is generally accepted to be about 1013 Poise. As the temperature is increased above Tg, eventually enough bonds break due to thermal energy, and the structure becomes sufficiently “liquid” that the glass will deform under an applied load and over a reasonable time scale. At this temperature and higher, the viscosity can be measured directly, and several different methods are required to cover the entire viscoelastic region, from the glass transition until the glass is fully melted. The measured viscosity will vary more than 10 decades, or 1010 over this range, which is a factor of 10,000,000,000 (Ten billion)!

In order to measure the sample length change, the dilatometer pushrod must be mechanically coupled to the LVDT sensor, and in so doing, it puts the sample under a compressive load. When the sample length changes, the LVDT senses this change via its mechanical connection to the pushrod. As the sample enters the transition region above Tg, eventually it will soften enough that the compressive force from the pushrod causes the sample to deform, counteracting the sample’s thermal expansion. When the deformation and the expansion cancel out, this is called the Dilatometric Softening Point (Ts). This is the peak temperature of the characteristic “hook” seen in Figure 5. At temperatures above Ts, the sample will deform further, resulting in an overall contraction of the sample in this direction. Thermal expansion measurements normally end soon after the Ts is reached so that the pushrod and sample do not become stuck together and ruined for further use or study.

In order to measure the viscosity at even higher temperatures, a different method would be selected; however, the dilatometer provides valuable insight into the glass properties. Many glass applications require the glass to bond with other materials, and often the glass must flow at least a little to make that happen successfully. Furthermore, in some critical applications, the glass must flow sufficiently, but not too much, so that the bonded part does not lose its shape. It is clear that a detailed understanding of the viscosity behavior is necessary, not only for selecting the best candidate glass, but also for developing a safe and effective temperature profile for such a bonding process. By using a pushrod dilatometer to precisely measure the CTE, Tg and Ts for a glass sample, the material scientist can discover a wealth of information about the thermal behavior for that particular glass composition and, in turn, can exploit that knowledge to develop tailored solutions for a range of glass and ceramic applications.

FAQ: Thermal Expansion of Glass

The CTE of glass varies by composition, is typically expressed in ppm/°C, and can be measured using pushrod dilatometer testing.

Ceramic thermal expansion testing is performed using dilatometry, which tracks dimensional change as a function of temperature.

Tg marks the approximate temperature boundary between the elastic behavior of a solid material and the time-dependent, or viscoelastic, behavior of a liquid.